The Genesis Files: Hashcash or How Adam Back Designed Bitcoin’s Motor Block

[ANNOUNCE] hash cash postage implementation

The date is March 28, 1997, when the 2,000-or-so subscribers of the Cypherpunks mailing list receive an email with the above header in their inbox. The sender is a 26-year-old British postdoc at the University of Exeter, a young cryptographer and prolific contributor to the mailing list named Dr. Adam Back. The email includes a description and early implementation of what he describes as a “partial hash collision based postage scheme” — a sort of stamp equivalent for emails, based on a nifty cryptographic trick.

“The idea of using partial hashes is that they can be made arbitrarily expensive to compute,” wrote Back, explaining the advantage of his system, “and yet can be verified instantly.”

This proposal by the cryptographer who would go on to become the current Blockstream CEO did not immediately garner much attention on the email list; just one reader responded, with a technical inquiry about the hashing algorithm of choice. Yet, the technology underlying Hashcash — proof of work — would shape research into digital money for more than a decade to come.

“Pricing via Processing or Combatting Junk Mail”

Back’s Hashcash was actually not the first solution of its kind.

By the early 1990s, the promise of the internet, and the advantages of an electronic mailing system in particular, had become obvious to techies paying attention. Still, internet pioneers of the day came to realize that email, as this electronic mailing system was called, presented its own challenges.

“In particular, the easy and low cost of sending electronic mail, and in particular the simplicity of sending the same message to many parties, all but invite abuse,” IBM researchers Dr. Cynthia Dwork and Dr. Moni Naor explained in their 1992 white paper bearing the name “Pricing via Processing or Combatting Junk Mail.”

Indeed, as email rose in popularity, so did spam.

A solution was needed, early internet users agreed — and a solution is what Dwork and Naor’s paper offered.

The duo proposed a system where senders would have to attach some data to any email they send. This data would be the solution to a math problem, unique to the email in question. Specifically, Dwork and Naor proposed three candidate puzzles that could be used for the purpose, all based on public-key cryptography and signature schemes.

Adding a solution to an email wouldn’t be too difficult, ideally requiring only a couple of seconds of processing power from a regular computer, while its validity could easily be checked by the recipient. But, and this is the trick, even a trivial amount of processing power per email adds up for advertisers, scammers and hackers trying to send thousands or even millions of messages at once. Spamming, so was the theory, could be made expensive and, therefore, unprofitable.

“The main idea is to require a user to compute a moderately hard, but not intractable, function in order to gain access to the resource, thus preventing frivolous use,” Dwork and Naor explained.

While Dwork and Naor did not propose the term, the type of solution they introduced would become known as a “proof of work” system. Users would have to literally show that their computer performed work, to prove that they spent real-world resources.

A nifty solution, but perhaps too far ahead of its time. The proposal never made it very far beyond a relatively small circle of computer scientists.

Adam Back and the Cypherpunks

Around the same time that Dwork and Naor published their white paper, a group of privacy activists with a libertarian bent came to recognize the enormous potential of the internet as well. The ideologically driven crowd started to organize through a mailing list centred around privacy-enhancing technologies. Like Dwork and Naor, these “Cypherpunks” — as they would come to be called — utilized the relatively new science of cryptography to work toward their goals.

Over the years, Adam Back — who earned his Ph.D. in 1996 — established himself as one of the more active participants on this list, at times contributing dozens of emails in a single month. Like most Cypherpunks, the cryptographer was passionate about topics including privacy, free speech and libertarianism, and engaged in technical discussions pertaining to anonymous remailers, encrypted file systems, electronic cash as introduced by Dr. David Chaum, and more.

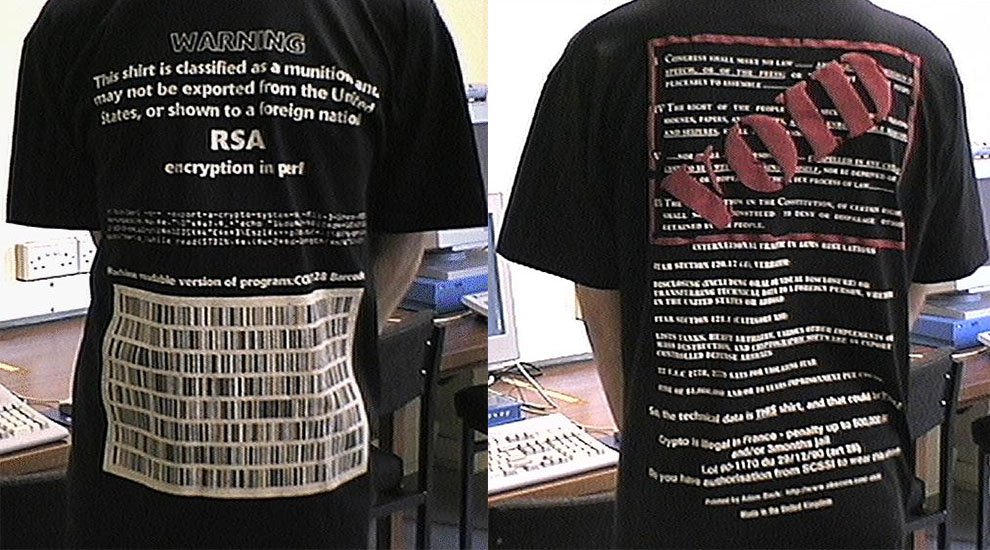

But for a while, Back was perhaps best known for printing and selling “munition” shirts: T-shirts with an encryption protocol printed on them, intended to help point out the absurd decision by the U.S. government to regulate Phil Zimmermann’s PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) encryption program as “munitions” within the definition of the U.S. export regulations. Wearing Back’s shirt while crossing the border to exit the United States technically made you a “munitions exporter.”

Like many, Back was not aware of Dwork and Naor’s proof-of-work proposal. But by the mid-1990s, he was thinking of similar ideas to counter spam, sometimes “out loud” on the Cypherpunks mailing list.

“A side benefit of using PGP, is that PGP encryption should add some overhead to the spammer — he can probably encrypt less messages per second than he can spam down a T3 link,” Back commented, for example, in the context of adding more privacy to remailers; an idea somewhat similar to Dwork and Naor’s.

The Cypherpunks mailing list grew significantly in about half a decade. What started out as an online discussion platform for a group of people that initially gathered at one of their startups in the Bay Area became a small internet phenomenon with thousands of subscribers — and often more emails on a single day than anyone could reasonably keep track of.

It was around this time — 1997, close to the list’s peak popularity — that Back submitted his Hashcash proposal.

Hashcash

Hashcah is similar to Dwork and Naor’s anti-spam proposal and has the same purpose, though Back proposed some additional use cases like countering anonymous remailer abuse. But as the name suggests, Hashcash was not based on cryptographic puzzles like Dwork and Naor’s; it was based on hashing.

Hashing is a cryptographic trick that takes any data — whether it’s a single letter or an entire book — and turns it into a seemingly random number of predetermined length.

For example, a SHA-256 hash of the sentence This is a sentence produces this hexadecimal number:

![]()

Which can be “translated” to the regular decimal number:

Or to binary:

Meanwhile, a SHA-256 hash of the sentence This, is a sentence produces this hexadecimal number:

![]()

As you can see, merely inserting one comma into the sentence completely changes the hash. And, importantly, what the hash of either sentence would be was completely unpredictable; even after the first sentence was hashed, there was no way to calculate the second hash from it. The only way to find out was to actually hash both sentences.

Hashcash applies this mathematical trick in a clever way.

With Hashcash, the metadata of an email (the “from” address, the “to” address, the time, etc.) is formalized as a protocol. Additionally, the sender of an email must add a random number to this metadata: a “nonce.” All this metadata, including the nonce, is then hashed, so the resulting hash looks a bit like one of the random numbers above.

Here’s the trick: not every hash is considered “valid.” Instead, the binary version of the hash must start with a predetermined number of zeroes. For example: 20 zeroes. The sender can generate a hash that starts with 20 zeroes by including a nonce that randomly adds up correctly … but the sender can’t know in advance what that nonce will look like.

To generate a valid hash, therefore, the sender has only one option: trial and error (“brute force”). He must keep trying different nonces until he finds a valid combination; otherwise, his email will be rejected by the intended recipient’s email client. Like Dwork and Naor’s solution, this requires computational resources: it’s a proof-of-work system.

“[I]f it hasn’t got a 20 bit hash […] you have a program which bounces it with a notice explaining the required postage, and where to obtain software from,” Back explained on the Cypherpunks mailing list. “This would put spammers out of business overnight, as 1,000,000 x 20 = 100 MIP years which is going to be more compute than they’ve got.”

Notably, Back’s proof-of-work system is more random than Dwork and Naor’s. The duo’s solution required solving a puzzle, meaning that a faster computer would solve it faster than a slow computer every time. But statistically, Hashcash would still allow for the slower computer to find a correct solution faster some of the time.

(By analogy, if one person runs faster than another person, the former will win a sprint between them every time. But if one person buys more lottery tickets than another person, the latter will statistically still win some of the time — just not as often.)

Digital Scarcity

Like Dwork and Naor’s proposal, Hashcash — which Back would elaborate on in a white paper in 2002 — never took off in a very big way. It was implemented in Apache’s open-source SpamAssassin platform, and Microsoft gave the proof-of-work idea a spin in the incompatible “email postmark” format. And Back, as well as other academics, came up with various alternative applications for the solution over the years, but most of these never gained much traction. For most potential applications, the lack of any network effect was probably too big to overcome.

Nevertheless, Dwork and Naor as well as Back (independently) did introduce something new. Where one of the most powerful features of digital products is the ease with which they can be copied, proof of work was essentially the first concept akin to virtual scarcity that didn’t rely on a central party: it tied digital data to the real-world, limited resource of computing power.

And scarcity, of course, is a prerequisite for money. Indeed, Back in particular explicitly placed Hashcash in the category of money throughout his Cypherpunks mailing list contributions and white paper, mirroring it to the only digital cash the world had seen at that point in time: DigiCash’s Ecash by Chaum.

“Hashcash may provide a stop gap measure until digicash becomes more widely used,” Back argued on the mailing list. “Hashcash is free, all you’ve got to do is burn some cycles on your PC. It is in keeping with net culture of free discourse, where the financially challenged can duke it out with millionaires, retired government officials, etc on equal terms. [And] Hashcash may provide us with a fall back method for controling [sic] spam if digicash goes sour (gets outlawed or required to escrow user identities).”

Despite the name, however, Hashcash couldn’t properly function as a full-fledged cash in itself (nor could Dwork and Naor’s proposal). Perhaps most importantly, any “received” proof of work is useless to the recipient. Unlike money, it could not be re-spent elsewhere. On top of that, as computers increased in speed every year, they could produce more and more proofs over time at lower cost: Hashcash would have been subject to (hyper)inflation.

What proof of work did offer, more than anything else, was a new basis for research in the digital-money realm. Several of the most notable digital-money proposals that followed were building on Hashcash, typically by allowing the proofs of work to be reused. (With Hal Finney’s Reusable Proof of Work — RPOW — as the most obvious example.)

Bitcoin

Ultimately, of course, proof of work became a cornerstone for Bitcoin, with Hashcash as one of the few citations in the Bitcoin white paper.

Yet, in Bitcoin, Hashcash (or, rather, a version of it) is utilized very differently than many would have guessed beforehand. Unlike Hashcash and other Hashcash-based proposals, the scarcity it provides is not itself used as money at all. Instead, Hashcash enables a race. Whichever miner is the first to produce a valid proof of work — a hash of a Bitcoin block — gets to decide which transactions go through. At least in theory, anyone can compete equally: much like a lottery, even small miners would statistically be the first to produce a valid proof of work every so often.

Further, once a new block is mined, confirming a set of transactions, these transactions are unlikely to be reversed. An attacker would have to prove at least as much work as required to find the block in the first place, adding up for every additional block that is found, which under normal circumstances becomes exponentially harder over time. The real-world resources that must be spent in order to cheat typically outweigh the potential profit that can be made by cheating, giving recipients of Bitcoin transactions confidence that these transactions are final.

This is how, in Bitcoin, Hashcash killed two birds with one stone. It solved the double-spending problem in a decentralized way, while providing a trick to get new coins into circulation with no centralized issuer.

Hashcash did not realize the first electronic cash system — Ecash takes that crown, and proof-of-work could not really function as money. But a decentralized electronic cash system might well have been impossible without it.

For more on the history of proof of work, also see hashcash.org and, in particular, hashcash.org/papers/.

This article originally appeared on Bitcoin Magazine.